Since I've been posting to clevelandpoetics a series of "haiku" (one a week) under the heading "52 Cleveland Haiku," I suppose it is incumbent upon me to answer the question of what, exactly, I think a haiku is, and is not.

A haiku is a short nature poem written in Japanese, written as seventeen syllables and incorporating a kireji, building on the form of the hokku as adapted by such haiku masters as Basho and Issa. That's fine, but of course I'm not writing in Japanese (my Japanese is just good enough to say " two beers, please," and " excuse me, where is the bathroom?"). So, what is a haiku in English?.

-- at this point haiku scholars are already jumping up to shout at me for saying that a haiku in Japanese has seventeen syllables. A Japanese poet couldn't even tell you how many syllables a poem has; "syllable" isn't a Japanese word. Rather, a haiku is a poem with seventeen "on," or Japanese sound-units; an on is similar, but not exactly the same as, a syllable. For the most part, though, this distinction doesn't make much of a difference; with a few exceptions, seventeen Japanese "on" is usually also seventeen syllables. But here is a critical distinction: Japanese on are always very short syllables. The Japanese language doesn't have long or complicated syllables; a word like "strengths"-- one syllable in English!-- just can't be transliterated into Japanese. As a result, a poem of seventeen syllables in English says a lot more than a poem of seventeen on in Japanese (in fact, scholars say that twelve syllables in English conveys about the same content as seventeen on in Japanese).

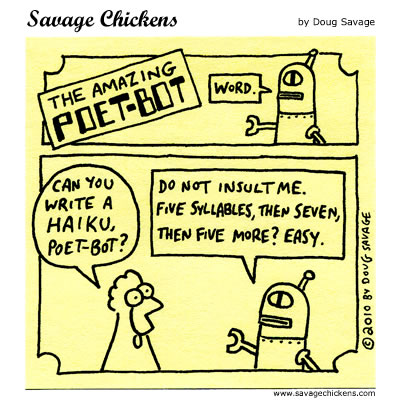

Classically, when haiku were adapted into an English form, they were formalized as a poem of three lines, respectively five, seven, and five syllables, for a total of seventeen syllables. This matches the pattern of a Japanese haiku, to the extent that it's even possible to do so, except that the Japanese poem is typically written in a single line, not three. But it results in a poem that, although short by English poetry standards, is still a lot longer than the elegant minimalism of the Japanese.

Add to this the fact that the Japanese haiku is not merely a syllabic form, but is a nature poem-- in fact, not merely a nature poem, but explicitly a seasonal poem (the "kigo" mentioned early is a season word). Traditionally, a haiku is "in the moment"-- present tense-- without metaphor, but simply observation; and also by tradition is not an imagined scene, but a direct experience by the poet.

Japanese has other forms for poems that aren't haiku-- senryu, for example, are also seventeen syllable poems, but poems of observation of human foibles. (Actually, I'm very fond of senryu, and a lot of the stuff in English that's tagged "haiku" are actually senryu.).

Haiku also have that "kireji" that I mentioned, a "cutting word" that cuts a haiku into two parts of five and twelve syllables (on). English doesn't have explicit "cutting words," but a traditional haiku in English will have a distinct pause, often made explicit with punctuation (e.g., a dash or a colon) at the end of either the first line (assuming it's written in three lines), or the second, thus cutting it into two pieces of either five and twelve, or twelve and five, syllables.

So, what about haiku in English, anyway? Because English syllables say so much more than Japanese on, an English poem of 5-7-5 syllables tends to be rather fat compared to a Japanese haiku. A haiku ought to be an observation that is stripped down to its essentials, but in English, the poet sometimes even has to add syllables to pad out the count up to seventeen. The Haiku Society of America now defines a haiku simply as "a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience of nature or the season intuitively linked to the human condition" -- note the fact that they have given up on the 5-7-5 form, and don't even keep the tradition of writing in three lines (nor, for that matter, the requirement for a seasonal reference.).

OK. Well, even in Japan, modern haiku poets often have given up the explicit seasonal reference-- and don't always write in the seventeen on, either. But, to be fair, they have a few centuries head start on us, and must be getting pretty tired of what can said in seventeen on using the list of allowed kigo and kireji words.

The 5-7-5 form, in English, has become almost a joke-- much of what passes for haiku in English is little more than zappai, "miscellaneous" or joke poems. It's very freeing to write a haiku and focus on stripping the words down to just the essentials, instead of obsessing over syllable count, trying to nail an image clearly and distinctly.

But, on the other hand, when a form is abandoned, something is missing. Despite the difference between English and Japanese, in Japanese a haiku is not just any short series of words, but a series of words in a particular pattern. So, sorry, HSA, but in giving up on 5-7-5, yes, something is gained, but also something essential is lost.

So, all in all, I have gone back to writing haiku into 5-7-5 form, although I have given up on being strict about it. And keeping a pause cutting the poem in two pieces. And, when it's explicitly a haiku (and not, perhaps, a senryu), a seasonal reference. --But the title "52 Cleveland Haiku" is figurative: although many of these (maybe even most) are haiku, I've sprinkled in some senryu, and, yes, probably even a few zappai.

Don't like it? Well, feel free write your own.

--Geoffrey A. Landis

- Also, don't forget to check out Joshua Gage's earlier post "Haiku and Cleveland"

7 comments:

I was lucky that David Lanoue taught me about haiku so I never got locked into the 5, 7, 5 thing. and I've done quite a bit of the experimental horror and Scifi Ku.

My wife writes haiku, and totally agrees both with your view on the art form, and that the HSA has lost its way to a point.

quote....The Haiku Society of America now defines a haiku simply as "a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience of nature or the season intuitively linked to the human condition."

This definition of a form of poetry, known for it's brevity, is ludicrous. Haiku is less, not more. Why would a Society dedicated to Haiku burden the form with such verbosity?

eeeee

To be fair, once must include the full HSA definition, including all the accompanying notes, which are very specific on things like syllable count in haiku:

Definition: A haiku is a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience of nature or the season intuitively linked to the human condition.

Notes: Most haiku in English consist of three unrhymed lines of seventeen or fewer syllables, with the middle line longest, though today's poets use a variety of line lengths and arrangements. In Japanese a typical haiku has seventeen "sounds" (on) arranged five, seven, and five. (Some translators of Japanese poetry have noted that about twelve syllables in English approximates the duration of seventeen Japanese on.) Traditional Japanese haiku include a "season word" (kigo), a word or phrase that helps identify the season of the experience recorded in the poem, and a "cutting word" (kireji), a sort of spoken punctuation that marks a pause or gives emphasis to one part of the poem. In English, season words are sometimes omitted, but the original focus on experience captured in clear images continues. The most common technique is juxtaposing two images or ideas (Japanese rensô). Punctuation, space, a line-break, or a grammatical break may substitute for a cutting word. Most haiku have no titles, and metaphors and similes are commonly avoided. (Haiku do sometimes have brief prefatory notes, usually specifying the setting or similar facts; metaphors and similes in the simple sense of these terms do sometimes occur, but not frequently. A discussion of what might be called "deep metaphor" or symbolism in haiku is beyond the range of a definition.

When this definition is applied to well translated haiku, with no extra language (as is often the case with Hamill, Henderson, occasionally Blyth, etc.) it is clear that 5-7-5 English syllables often cannot work as haiku, simply because too much information is put into what should be a simple and immediate poem.

Blyth, who is a great scholar of haiku despite some of his translation issues, offers a 2-3-2 accentual solution. Haiku, Blyth argues, is a clipped form of the Choka line, which was a 5-7 line and a "standard" in Classical Japanese poetry. The tanka, for example, was 5-7-5-7-7, the double seven line indicating a closure of sorts. The 5-7-5 of a haiku was meant to feel unresolved, incomplete, or open ended, waiting for a 7-7 line to finish it. Blyth, assuming that the iambic pentameter line is similarly the "standard" line of English, proposes accentual 2-3-2 lines for haiku in English, which theoretically would produce the same unresolved or open ended feeling in the reader.

A lot of this is explained in William J. Higginson's The Haiku Handbook, which is an essential resource for anyone who is considering writing haiku in English. I'd also recommend Gurga's Haiku: A Poet's Guide and How to Haiku by Bruce Ross. Of course, reading modern haiku, be it online magazines like The Heron's Nest or books from Red Moon Press and Brooks Books Press should also be considered essential. Many of these books are available through OhioLink via the Cuyahoga County Library system.

Point taken.

Every time I tried to write a one-line sentence statement about haiku, it turns out into an essay. And every time I start out trying to say one thing, I keep on want to say "but on the other hand..."

Point proven.

A sliver of glass

in Basho's eye magnifies

his simple vision.

Post a Comment